Disruptions are here to stay

The response to COVID-19 forced countries to divert scarce healthcare resources towards managing the immediate effects of the novel coronavirus, and away from other therapeutic areas including cancer care. This led to 15 new delays in patient access to cancer care across Europe, which added to the 10 systemic factors which were already delaying patient access to oncology prior to the crisis.

Though the current crisis has been a once in a lifetime event for most healthcare professionals, it is important to realise that disruptions are here to stay. Future disruptions or sustainability challenges could come for example from:

- a new COVID mutation, or a completely new pandemic

- the looming crisis in antimicrobial resistance

- the alarming (and increasing) chronic shortage of healthcare personnel

- growing demand for healthcare due to ageing populations in a context of finite healthcare budgets

What have we learned from COVID-19?

Though the pandemic has significantly disrupted patient access to oncology care, it has also served as a catalyst for new, improved healthcare techniques, models, partnerships and policies in cancer care.

In the first months of 2021, we worked together with a broad group of almost 20 cross-stakeholder organisations around Europe, including investigators, government agencies, pharmaceutical companies, professional societies and patient organisations, to capture the positive developments which should be maintained and adopted instead of going back to the old normal.

If these learnings and innovations are heeded, they can help ensure improved patient access to cancer care for generations to come, by:

- Freeing up scarce hospital capacity

- Reducing waiting times for in-person visits

- Improving health care access and convenience

- Ensuring efficient use of public resources.

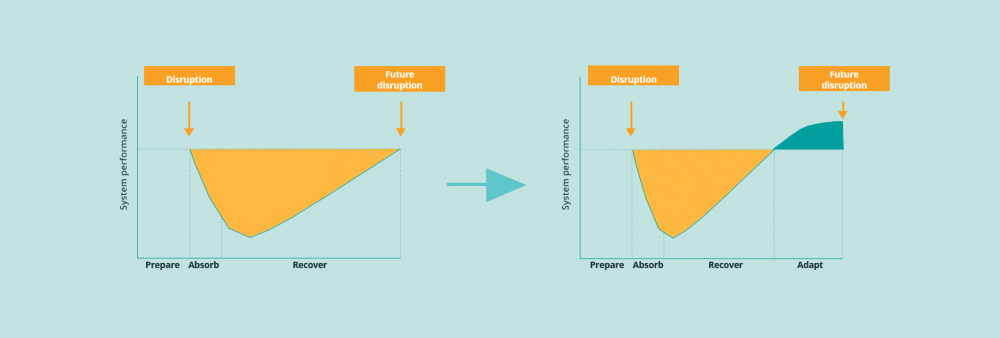

This will allow European health systems to optimally recover and adapt to improve performance of oncology care in Europe. Because for cancer patients and their loved ones every day counts, no matter how serious the threat to normal healthcare processes.

Our six recommendations

-

Clear the cancer backlog now, using innovative practices which emerged during the pandemic

While health systems have been able to absorb some of the impact of the crisis while mitigating the impact on cancer patients, there will be a significant backlog of cases as they move to the recovery phase. This backlog will further delay both a return to normal cancer service levels and the implementation of improvements resulting from the learnings gained during the pandemic.

The following new experiences and structures developed as a response to COVID-19 could be used to clear the backlogs in cancer screening and treatment:

- The extensive infrastructure and public-private partnerships that were put in place for COVID-19 testing and vaccination (e.g. drive-in centres).

- The use of techniques like “teledermatology” as a screening tool

- Amended treatment schedules to avoid hospital visits and resulting side effects.

- New diagnostic tests such as molecular profiling and liquid biopsies can replace bronchoscopies and surgical interventions in lung cancer to quickly and efficiently provide a diagnosis with minimal interaction from healthcare professionals.

-

Maintain the proven agility of R&D and Marketing Authorisation processes

Cancer researchers have sought ways to keep trials running as much as possible, especially for therapies which show a clear potential clinical benefit and have no viable substitutes. COVID-19 has catalysed the use of innovations which could be helpful in the future, especially for clinical trials in rare cancers or rare genetic targets. These trials are often made difficult as few patients are able to reach the clinical trial site.

The innovations include:

- Signing consent forms electronically and remotely

- Mailing oral cancer drugs to patients’ homes

- Piloting devices which allow patients to draw their own blood

- Increasing the use of telemedicine and digital tools to monitor patients and collect data

At the level of the European Medicine Agency (EMA), rolling reviews were introduced to speed up the assessment of promising medicines or vaccine candidates We should learn from this process, which was introduced to streamline regulatory processes for marketing authorisation for future breakthrough therapies in oncology, rather than returning to the old ways.

-

Continue intensified European collaboration in clinical assessment to use scarce HTA resources more efficiently after the pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic and related vaccine development have clearly shown that joint clinical assessments are possible. The political agreement reached by the European Parliament and the Council of Ministers on the Portuguese Presidency’s Proposal for a Regulation on Health Technology Assessment is an important step towards formalising these joint clinical assessments. The key challenge is for the new system to become a predictable, efficient, non-duplicative system which is ready to assess current clinical pipeline outputs which are changing treatment paradigms radically. We should make maximum use of the learnings from the pandemic in moving towards this new system.

Greece introduced an e-prescription process in March 2020, which allowed patients to receive specialist cancer prescriptions without attending hospital (EOPYY, 2020). This was complemented by allowing patients to receive medicines usually dispensed in hospitals from community pharmacies (EOPYY, 2020b&c).

-

Continue the adoption of digital health to increase remote care and use healthcare resources more efficiently after the pandemic

One of the developments which has most been catalysed by the pandemic is the use of telemedicine:

- In France there was a 50-fold increase in teleconsultations between 23 and 29 March 2020 compared to the situation in the previous months.

- In Germany, the number of teleconsultations performed in March 2020 was estimated to be 11 times higher than the average for January and February 2020.

- In Norway, the proportion of e-consultations carried out primary care increased by a factor of 12, from 5% between 2 and 8 March to almost 60% between 16 and 22 March 2020.

Telemedicine is a crucial enabler to allow various (oral and subcutaneous) medical treatments, as well as blood testing and some follow-ups, to be transferred away from the traditional hospital setting. This will make health systems more future proof, in a context of Europe’s health systems struggling to absorb increases in caseload caused by COVID-19 and ageing populations.

In Portugal, the government allowed the delivery of medicines, which were previously dispensed in hospitals, via community pharmacies or straight to the home (Ordem do Médicos, 2020).

-

Maintain and build adaptive surge capacity to be ready for future disruptions to cancer care

Health systems must learn from their experiences to be better able to respond to future surges in demand.

As it may be neither possible nor efficient to scale up structural resources, the challenge is to instil flexibility and agility to allow both a rapid response to disruptions and the continuance of regular activities as far as possible.

A lack of health personnel is likely to be the major constraint on increasing flexibility, due to the time required to train skilled health professionals. But even here, countries have found creative solutions:

- France mobilised and expanded its existing pool of Réserve Sanitaire healthcare staff, while Belgium, Iceland and Ireland quickly set up new “reserve lists” to deal with the outbreak and reallocate staff across localities

- At least half the countries in Europe recalled inactive and retired health professionals. Most countries mobilised students nearing the end of their studies to assist the population via telephone hotlines and support service delivery. In Italy, military healthcare professionals supported service delivery in hospitals.

- Sweden encouraged flight attendants and redundant personnel from other sectors badly hit by the pandemic to retrain in order to help hospitals deal with the coronavirus crisis.

- Countries also accelerated the implementation of policies to balance the skills mix between healthcare professionals:

In Austria, France, Ireland, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom, pharmacists can now prescribe chronic medications, and have been given greater power to extend prescriptions.

-

Protect cancer budgets to ensure the continuity, efficiency and sustainability of cancer care.

Over the last 20 years, cancer spend has not increased as a proportion of total health expenditure, despite increasing cancer incidence rates. At the same time, survival rates and productivity have both increased, thanks to advances in treatments and care delivery models.

This balance is under now under pressure. Following the pandemic, the risk of new health cost-containment measures and potential reallocations of budgets away from oncology towards infectious diseases could lead to austerity measures and harsher prioritisation decisions to reduce already tight budgets for cancer care still further.

One key learning from the COVID-19 crisis is that investing in strong and resilient health systems is crucial to mitigate the impact of external shocks on the wider economy. The healthcare austerity measures put in place after the global financial crisis in 2008 should not be repeated this time.

Investing in healthier people who can carry on working helps drive healthy economies. A strong commitment is needed in order to maintain even current investment levels and the progress already made in terms of life expectancy and productivity. Safeguarding and optimising the use of health and cancer care budgets, by combining improvements in efficiency with investments in innovation, is a key prerequisite for using the learnings from the crisis to improve cancer care.

We must build on the COVID-19 momentum

COVID-19 vaccines were developed, licensed, produced, distributed and given to patients at record-breaking speed, while at the same time emergency access to care was protected. This shows how stakeholders can join forces to solve serious challenges successfully and still provide rapid patient access. A common goal, a sense of urgency, mutual trust and the combination of efforts allows us to break down silos and refocus often divergent interests.

Now is the time to prioritise these recommendations to reduce access delays for today’s cancer patients, and minimise the impact of future crises on those of tomorrow!

LET’S DISCUSS

Inspired to share your thoughts? Or would you like to learn more on how to implement the learnings from the pandemic? We would be delighted to hear from you. Please feel invited to contact Bas Amesz.

DO YOU WANT TO READ MORE?

Please also be invited to read the articles in our “Every day counts” blog series, which we published previously:

- White paper release: Every day counts

- Blog: Bringing stakeholders together to improve patient access to oncology therapies in Europe

- Blog: European access discussions shouldn’t stop at reimbursement

- Blog: Deep dive: The Patient Access Indicator

- Blog: The 10 key factors delaying patient access across Europe

- Blog: Introducing new cancer treatments: how reducing time to Market Access dramatically impacts patients’ lives

- Blog: Speeding up patient access requires dealing with uncertainty on clinical value first, negotiating price second